History of Piano Concerto, Op. 21

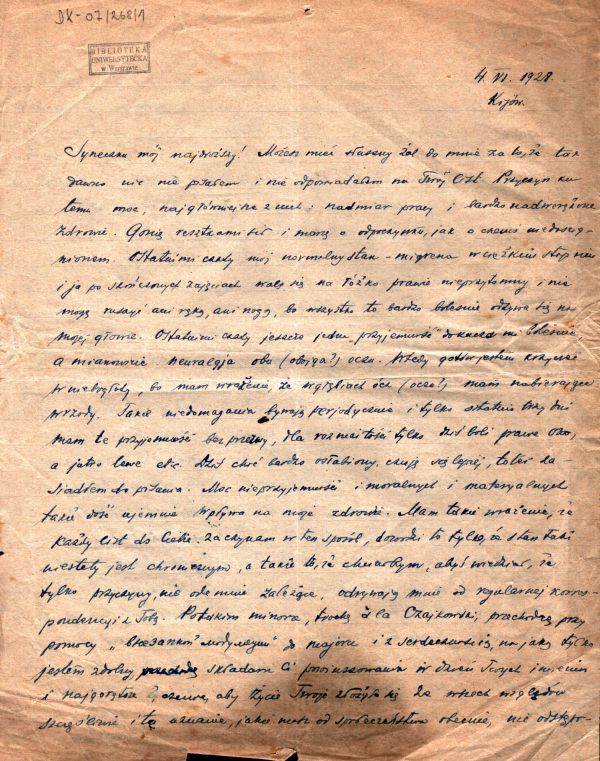

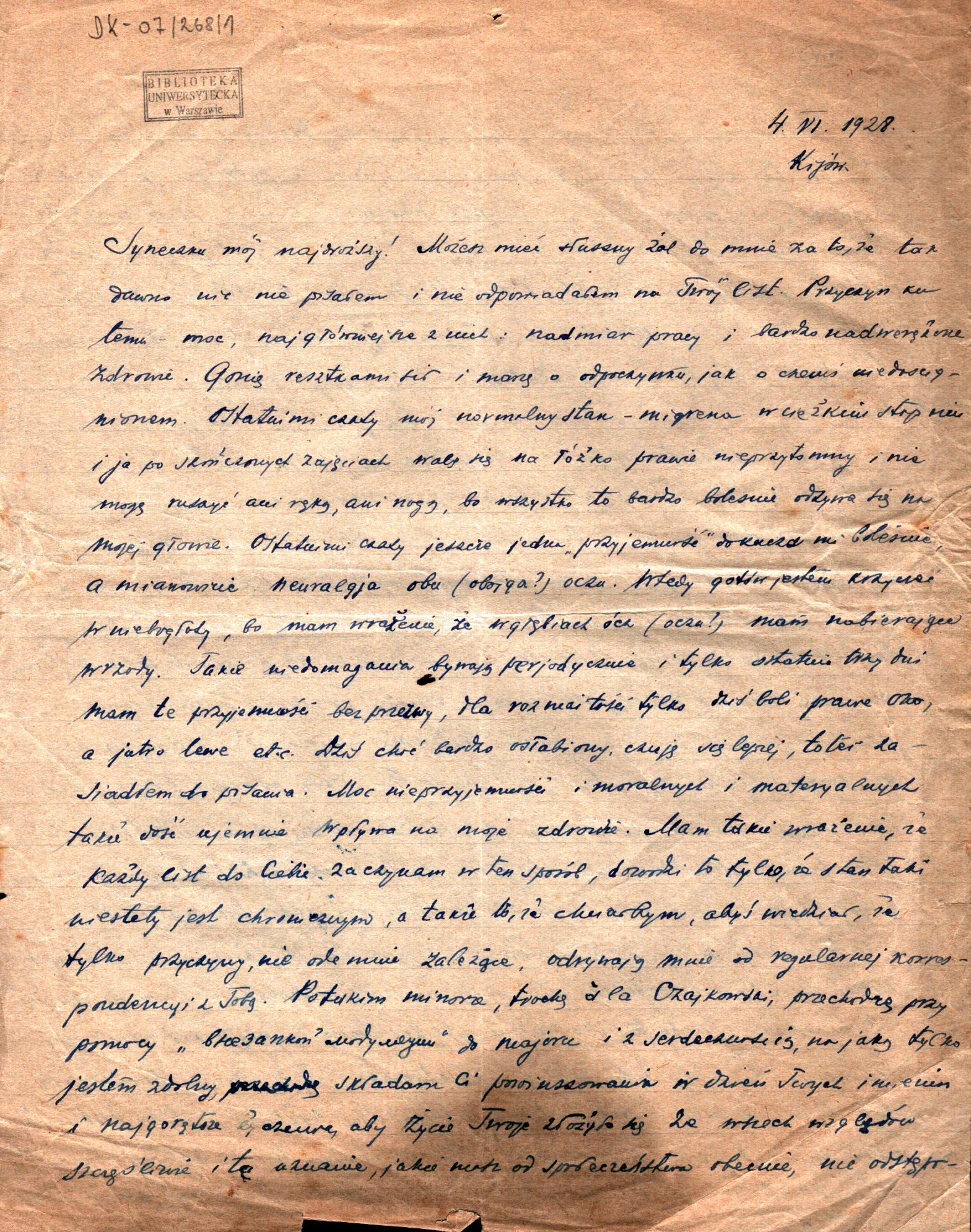

In a letter to his son in Warsaw, dated 4 June 1928 and starting with the words ‘My Dearest Son!’, Régamey the father confesses:

Conducting and composition are my profession. The time has become late to compose, and I will only write to satisfy my internal needs. As regards conducting, I may take it up seriously in this old age as long as my health allows me.

Régamey Sr believed in music. He recounted his career in Kyiv, hoping that his son, who was then studying in Warsaw, would not give up music, develop his abilities, and eventually become a composer like his himself. In another letter to his son, whom he missed very much, penned on 20 September 1934, Régamey Sr writes:

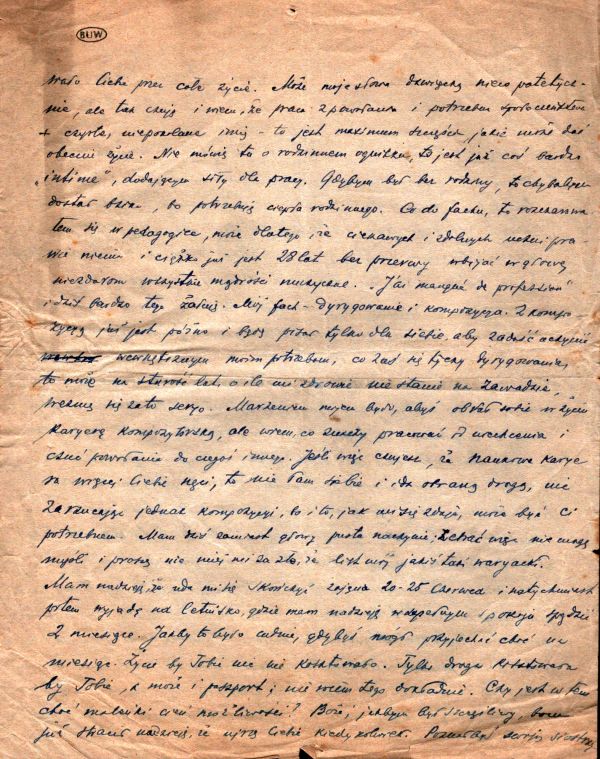

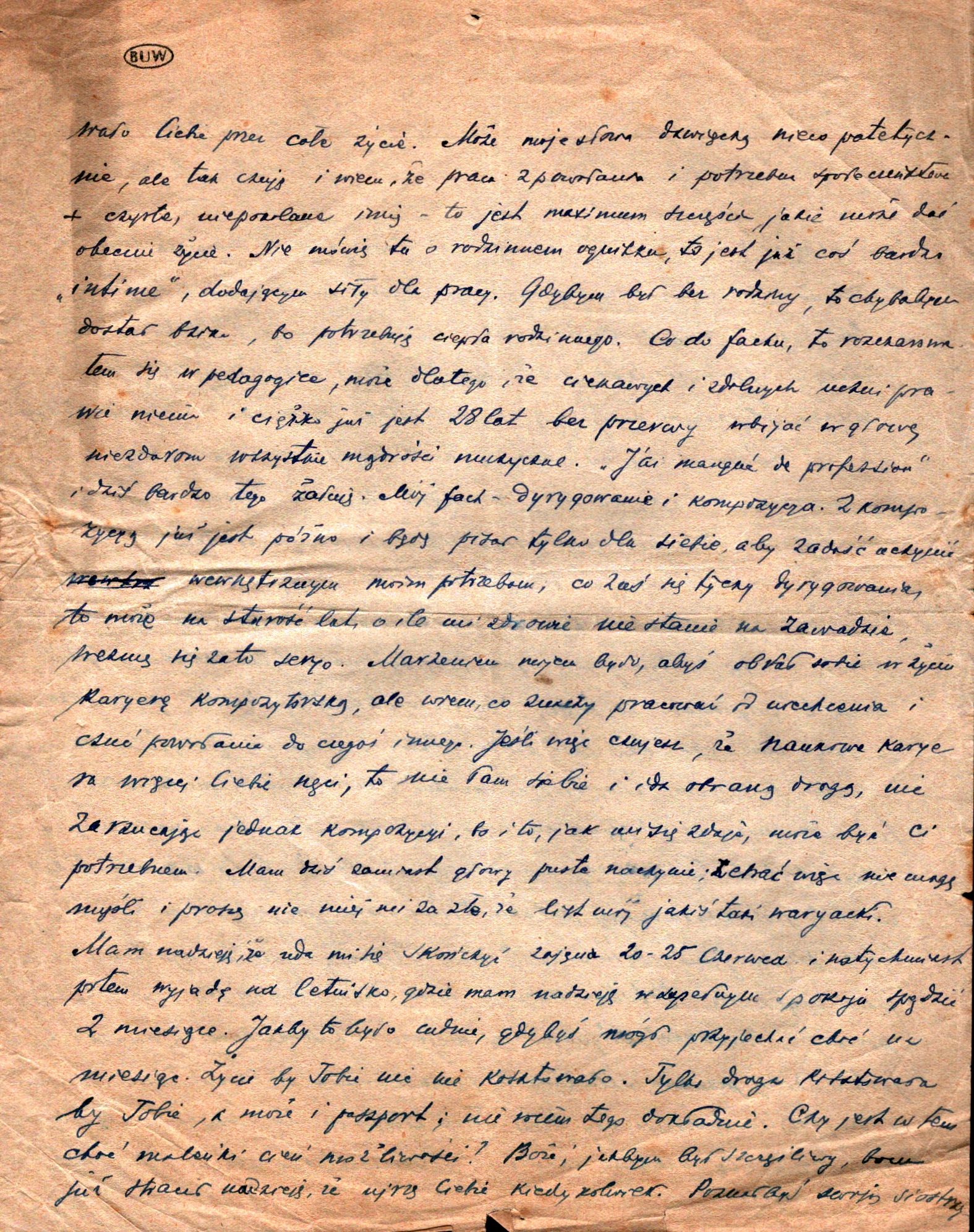

As regards Your music […] I really want to hear You playing. I have never heard You play, not at all, but I was told that You play beautifully. How about playing the concerto for two pianos together? Have you ever tried to play my piano concerto? I will probably soon present it at the Union of Soviet Musicians of Ukraine, of which I am a secretary in charge…

This is one of the few if not the only piece of evidence that Régamey Sr also composed a piano concerto, apart from the numerous salon songs and instrumental miniatures written and published before the Soviet Revolution. He probably worked on his concerto in the mid-1920s, after the ravages of revolution and civil war were over, and he had recovered from his health crisis in Taganrog. He had again found some stability as a highly regarded professor at the Lysenko Institute and was much sought after as a pianist-accompanist. On the other hand, he may not have been quite satisfied with these successes since in another place he complains of being tired of, and disappointed with teaching. After all, it was only ‘conducting and composition’ that he saw as his profession.

How the manuscript of his concerto found its way to his son in Warsaw is unknown. Considering the problems with mail circulation between the Soviet Ukraine and ‘bourgeois Poland’, it may be conjectured that the score was entrusted to some friend or acquaintance returning from Kyiv to Poland. One such a person was the singer Ewa Bandrowska-Turska (‘we were visited by Bandrowska, who delighted us with her wonderful voice’), Régamey Sr’s friend, who sometimes came with concerts to Kyiv, where she enjoyed great fame. Grzegorz Fitelberg also frequently visited Kyiv. Régamey Sr describes him as ‘the chief conductor of Kyiv Radio Broadcasting Committee’, where he himself appeared in broadcasts but also worked as ‘senior concertmaster [in the sense of accompanist] in charge of six pianists-accompanists’.

Whatever the case, the score of the concerto presumably reached Regamey Jr long before 1934. At the outbreak of World War II, he lived in Warsaw and soon began to take part in underground life. He would use his Swiss papers to travel by train to the house of his wife Hanna Kucharska in Cracow, then the capital of the General Government. It was there that he began to write Persian Songs, his first composition after a long break (i.e. since 1932). In Cracow under the German occupation, he also took part in social life, meeting, among others, Prof. Zdzisław Jachimecki. Focusing more intensely on music during the war, Regamey must have taken the manuscript of his father’s work from Warsaw to Cracow, thus probably saving it from the fires of Warsaw Uprising. It is therefore not entirely surprising that the manuscript was miraculously rediscovered in Cracow when the flat of Konstanty’s sister-in-law Danuta Kucharska was being cleared seventy years after the outbreak of the war.

The recovered manuscript comprises fifty-seven pages (with poorly legible pagination in pencil) and was written in ink on thick, already quite old manuscript paper produced by a Moscow printing house. Fol. 1r includes the title ‘Concerto fis-moll’ [in F-sharp minor] and, at the top, the dedication, ‘Dedié a Monsieur Reinhold Glière’ along with the composer’s signature and opus number: ‘C. Régamey, Op. 21’. Fol. 1v repeats the same information (i.e. dedication, title, surname, and opus number). Movement One is marked with the Roman numeral ‘I’ and the words Allegro con spirito, indicating tempo and expression. The first chord progression bears the instruction pesante.

Jerzy Stankiewicz, "The Forgotten figure...